It starts with a beep, a buzz, or a gentle shake. Your diabetes medical device wants your attention.

It’s like hearing someone call your name across a crowded room. What’s your response? Do you look at your diabetes device with curiosity? Or with dread? Do you even look at the alarm? Or do you simply push the acknowledgement button and continue on with what you were doing?

Diabetes device alarms are intended to give you a heads up. Something, related to your diabetes, needs your attention. They’re meant to be helpful. But are they?

When Diabetes Device Alerts Lead to Alarm Fatigue

We’ve all experienced less-than-helpful alerts.

The ones that simply repeat again and again. “Recurring pattern found…”

The ones that say the obvious. “Your blood sugar [sic] has been High [sic] between 11:30 AM and 12:15 PM.”

The ones that point to a dead-end instead of something actionable. “A recurring high pattern has been detected during this time for the past 14 days.”

By the 14th day (of adjusting your routine and still seeing the same alert), it feels more like a nag than a helpful prompt. The mental, emotional, and spiritual fatigue that comes from responding to the same thing over and over without any shift in results kills any motivation that might remain to respond. It leaves you stuck. This is what alarm fatigue looks like.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Alarm fatigue can be avoided. When people are the focus of the design and development of diabetes devices, alarms can alert the user and lead them toward taking timely, appropriate, and effective action—with the goal to keep the person confident and secure in their diabetes self-care and management.

Understanding What Leads People to Take Action

The point of having a diabetes device issue an alert is to get the user to take an action. The alarm is saying, in effect, “Hey! Something to do with your diabetes needs your attention and you need to do something. Right now!”

For an alarm to work as expected it has to be based on how and why people act or change their behavior. It also needs to take into consideration how that response can be undermined or disrupted.

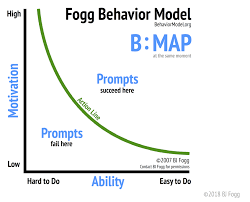

B.J. Fogg, in his behavior model, identifies three things that need to be present for a behavior to take place: a prompt, motivation to do something, and the ability to respond.

The Fogg Behavior Model identifies three primary factors needed for a person to take action: Motivation, Ability, and a Prompt. | Source

With diabetes devices, the alarm takes on the role of the prompt. It gets the person’s attention and cues them to take some action. To be effective, the alarm cannot undermine the person’s feelings of motivation or ability to respond. Else the alarm will fail to prompt the desired response.

There are a number of ways alarms can undermine motivation and lead to alarm fatigue. An alarm that repeats again and again either in quick succession or over days ends up nagging the user instead of motivating them. When the language used in the alert message is condescending or judgmental, it leaves the user feeling disempowered and apathetic.

Poorly designed alarms can also undermine the user’s ability to respond. One example is an alarm that suggests a large, complex action like “Consider how you can reduce the stressors in your life today.” Another example is having the alarm urge the user to take an action that cannot be done in their current situation, like prompting a sensor change while the user is driving.

In Bigfoot Biomedical’s virtual modeling environment (called vClinic), we simulated whether outcomes on one of our systems in development would be better or worse if a user receives and acknowledges an alarm or not. In one recent simulation, we created an alarm system defined by clinical expertise, and then tried 12 different design choices. In that simulation, we reduced the number of alerts by ~25% and improved simulated clinical outcomes by ~30%.

Designing Actionable Alarms for People

When taking a people-first look at diabetes devices, developers may find themselves making trade-offs between what’s technologically possible and what truly serves the individual. Users may find themselves looking for specific capabilities in their diabetes devices. More may not be better. “Always-on” may not always be helpful.

The purpose of alarms is to help people respond appropriately and effectively to minimize risk and harms. To do this successfully, how and when the device alarm is triggered needs to be based on more than just the raw data presented by a glucose reading or the state of a sensor.

The alarm function must be designed so that the person can act on the alarm quickly and easily. Taking the situational context into account supports making the alarm actionable throughout the person’s day, not just in the ideal circumstances.

Many different factors influence a person’s situational context. Physical location and time of day are two of the most obvious. The example above, where the person gets a sensor warning while driving, demonstrates how physical location can work against resolving an alarm immediately. Time of day is another contextual factor that may affect a person’s ability to respond. Should the low glucose alarm be the same (in sound, volume, and duration) at two in the afternoon as at two in the morning? What if the person works the overnight shift?

Some common alarms might even be considered for elimination or designed with the option to turn them off. Take ordering supply refills, for example. Does the person really have to be actively involved in that action? Or could a device keep track of how many supplies have been used, automatically order refills when needed, and let the person know more supplies are on the way after the device has submitted the order?

By understanding a person’s daily reality and then designing diabetes devices to work within that reality, device makers have the potential to become more than just device suppliers. They have the potential to become a real-time partner in your diabetes self-care and management.